Flash back: You’re 16, gripping the steering wheel of your first car. Maybe it was used, maybe it was new, maybe it was just your parents’ car, but it didn’t matter. You were behind the wheel, the windows were down, the radio was up—and you were just so free.

Driving is one of those major life skills that ushers you into adulthood—which is why it can be difficult for senior adults to give it up, even when it’s no longer safe for them to drive.

“Driving allows us to maintain our independence, especially here in the United States, where it’s one of the major modes of transportation,” said Dr. Nidhi Gulati, a family medicine physician at Augusta University Health and medical director of the Georgia War Veterans Nursing Home.

“But just like we retire from our jobs, for some seniors, there comes a point when we need to retire from driving.”

Ready to retire?

While there are many age-related changes that can result in a decreased ability to drive—or to drive safely—some are more apparent than others.

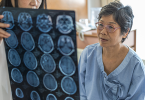

Neurological disorders, sensory and visual changes, and orthopedic issues are among those obvious reasons why someone should no longer be behind the wheel.

But cognitive declines, including losses in intuition, judgment and memory, can happen gradually and are a little harder to determine, said Gulati. Still, there are red flags that family members can look out for:

- Have loved ones gotten lost while driving, especially going to places they visit frequently?

- Have they made driving mistakes, such as not stopping at red lights or making a right turn from the left lane?

- Are there little fender-benders or nicks and dings on their car, or have you found tickets for moving violations? Or, have there been actual accidents?

Also, older family members may try to assure their relatives: “My driving’s fine; I go to the bank, the grocery store and to church, and I’m really good at that.” Great, it sounds as though your loved one is practicing safe driving.

“Actually,” Gulati said, “that should really raise your antenna. It’s called self-reported avoidance, where someone limits their driving by where they are going or when they are going. In other words, your family member knows there’s a problem and that’s why they are limiting themselves.”

The right age

Currently, there is no national guideline to determine if seniors are safe to drive. Some states, like Illinois, require seniors older than 75 years of age to take an on-the-road driving test. But in Georgia and South Carolina, anyone can renew their driver’s license every five years, regardless of age (unless a driver has four crashes within a 24-month period, but drivers then only need to retake the written exam).

The question of when a senior should stop driving is a difficult one to answer.

“For example, 16 is an arbitrary age for when we should start driving,” Gulati said. “There are many 16-year-olds who are not mature enough to be on the road, yet if they can pass the exams, they are given a license. At the same time, some 70-year-olds may be fine on the road, while other 65-year-olds are not.”

In 2012, Preston Carter made national news when he reversed instead of going forward and backed into a group of elementary school students. Thankfully, no one was killed. Carter’s age according to his active driver’s license? 100.

Handing over the keys

Is it time for you to have a serious talk with your loved one about his or her driving? While it can be a tough conversation, try to frame it positively.

“For example, there came a day when you retired from your job. It may be time now to retire from driving,” said Gulati.

It’s important to focus on the fact that your main concern is keeping your loved one safe. Also, you can also talk about other options: Maybe you and other family members or friends can set up a driving schedule so that loved ones can still go on their regular grocery runs and other routines.

“The goal is to explore the support systems that are in place and alternate means of transportation so that seniors don’t get isolated and depressed,” said Gulati.

If your loved one still insists they are fine, you can also suggest going in for a driving evaluation just to make sure. Your doctor can refer you to an occupational therapist—or the easiest route is just to visit your local DMV. If your loved one passes, that eases everyone’s mind. If not, then that’s a good thing too.

Worst-case scenario, if your relative refuses to give up driving and you know they are a hazard to themselves and to others, you may need to report them to the DMV. Physically taking away their keys, disconnecting the car battery or taking the license plate (so that if they are able to get on the road, they are more likely to be stopped) are also options of last resort.

“You never want it to get to that level,” Gulati said, “but on the flip side, if your loved one has significant physical or cognitive deficits that affects their driving and continues to insist on getting out on the road, there is a responsibility to get involved. There are numerous cited cases of catastrophic accidents involving seniors. No matter how you approach this sensitive issue, do it out of love, respect your loved one’s feelings, but make sure they stay safe when it comes to driving.”

Seek counsel from a geriatric medicine specialist

We’re here to help you or your loved one determine whether or not it’s time to retire from driving. To find a doctor who specializes in geriatric medicine or schedule an appointment at Augusta University Health, visit augustahealth.org, or call 706-721-2273 (CARE).